The Hemingway Patrols: Ernest Hemingway and His Hunt for U-Boats

“The Hemingway Patrols is modest in length and epic in scope. Writing in a limpid, economical prose that his subject would admire, Terry Mort tells the story of a little-known period in the life of one of America’s greatest novelists and manages to weave all sorts of disparate threads into a harmonious whole. Descriptions of submarine warfare and naval battles alternate with insightful commentaries on Hemingway’s art and career and portraits of his troubled marriage to his third wife, the fascinating Martha Gellhorn. There is even a poetic treatise on celestial navigation. Like a well designed memory chip, this book crams an awful lot into a small space and does so with elegance and grace.” — Phillip Caputo, Author of A Rumor of War

![]() [SYNOPSIS] A fascinating account of a dramatic, untold chapter in Hemingway’s life—his pursuit of German U-boats during World War II. From the summer of 1942 until the end of 1943, Ernest Hemingway lived in Havana, Cuba, and spent much of his time in the Gulf Stream hunting German sub- marines in his wooden fishing boat, The Pilar. This phase of Hemingway’s life has only been briefly touched upon in biographies of Hemingway but proved to be of enormous importance to him. At the time, the U-boats were torpedoing dozens of Allied tankers each month and threatened America’s ability to wage war in Europe. Hemingway’s patrols were supported by the U.S. Navy, and he viewed these dangerous missions as both patriotic duty and pure adventure. But they were more than that: they provided some literary basis for The Old Man and the Sea and Islands in the Stream.

[SYNOPSIS] A fascinating account of a dramatic, untold chapter in Hemingway’s life—his pursuit of German U-boats during World War II. From the summer of 1942 until the end of 1943, Ernest Hemingway lived in Havana, Cuba, and spent much of his time in the Gulf Stream hunting German sub- marines in his wooden fishing boat, The Pilar. This phase of Hemingway’s life has only been briefly touched upon in biographies of Hemingway but proved to be of enormous importance to him. At the time, the U-boats were torpedoing dozens of Allied tankers each month and threatened America’s ability to wage war in Europe. Hemingway’s patrols were supported by the U.S. Navy, and he viewed these dangerous missions as both patriotic duty and pure adventure. But they were more than that: they provided some literary basis for The Old Man and the Sea and Islands in the Stream.

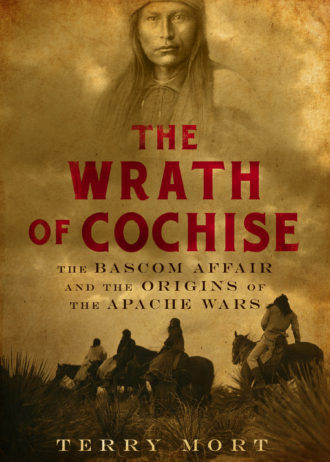

Introduction: Apache Pass lies between the Dos Cabezas and Chiricahua mountain ranges in southeastern Arizona. There in February, 1861, an incident occurred that started a war between the Chiricahua Apaches, on the one side, and the U.S. Army and white settlers of Arizona and New Mexico, on the other. It was not war as the whites understood it. There were no major battles in which large numbers of troops and warriors were engaged. It was a guerilla war. Attacks were often made against innocent non-combatants – on both sides. The Chiricahua effectively used their mobility and knowledge of the vast southwestern geography to frustrate the far less nimble U.S. army, so that the army’s greater manpower and firepower were nullified for much of the conflict. The first phase of this war lasted more than ten years — until 1872 — with devastating costs in lives and property. There followed a two year period of peace, but war broke out again and did not end until 1886 with the capitulation of the last remnants of the Chiricahua and their removal to a prisoner of war camp in Florida.

The broad outlines of this decades-long war are generally well known, as are the names of the principal Apache leaders – Mangas Coloradas, Geronimo, Juh, Nana, Victorio, and, perhaps most famous of all, Cochise. And it was Cochise who was there at the start of things, there in Apache Pass in 1861 when he was confronted by and, in turn confronted, a young army officer named George Bascom.

At the time of the incident Cochise was in his forties, perhaps late forties, although no one knows precisely the year he was born. He was the leader of his immediate circle, called a ‘local group,’ but he was not as yet the all powerful war chief that he would become. He had rivals among the Chiricahua – men who led their own respective local groups and who were sometimes at odds with Cochise. He also had allies, such as his father-in-law, Mangas Coloradas, who cooperated with Cochise politically and militarily. The decentralized social and political structure of the Chiricahua, and indeed of all the Apache tribes, meant that alliances and enmities often shifted according to the success in war and raiding enjoyed by one leader or another. And the Apaches were not immune to jealousies and political rivalries. A leader’s personality and rhetorical skills also affected his standing among his people and bolstered – or limited — his ability to rally other groups to his standard.

So in 1861 Cochise was one of many ‘chiefs’ and did not have the kind of political power over the wider population of Chiricahua that he would later achieve during the subsequent war against the whites. There are few contemporary accounts of him at this period, and those that exist are unflattering. Butterfield stage agent and subsequent Arizona Ranger, James Tevis, knew Cochise at this time and described him as treacherous, dangerous and untrustworthy. But Cochise successfully led his people in guerilla war for ten plus years and when he finally agreed to make peace – largely on his terms – the army officers and civilians who met him then were impressed by his gravitas, his honesty and his dignified implacability, to say nothing of the iron fisted command he exercised over his people – truly a unique situation among the independent-minded Apaches. Thus his reputation today is largely based on these later accounts – and with good reason, for he did keep his word to restrain his warriors when he made peace in 1872, and it was only after his death two years later that war broke out again. It’s fair to suggest, therefore, that the man at the beginning of the war was somewhat different from the man who ended it. Ten-plus years of fighting will change anyone. That may help to explain the inconsistencies in his story, for the barbarities he committed during the war are in sharp contrast to his statesman-like conduct and demeanor in the last two years of his life.

Whereas the reputation of Cochise has grown over the years, the reputation of his antagonist, Lieutenant George Bascom, has gone in the opposite direction. Indeed, Bascom is generally blamed for shattering the delicate relationship between the Chiricahua and the U.S. government and army. In fact, Bascom is invariably portrayed as a stereotypical young army officer whose blunders and poor judgment led to a conflict that turned out to be disastrous to the white civilians in the territory and ultimately to the Apaches, as well.

Thus the accepted history of the incident has given us the two main characters – Cochise, a leader admired for his tenacity, regal bearing and command, and George Bascom, an inexperienced officer who, when given the chance, made all the wrong decisions. There is a grain of truth in these characterizations, but as usual with binary constructions, the whole truth is rather more complicated. One of the objects of this book is to examine as much as possible the reasons the two main characters acted the way they did.

Further, the Bascom Affair, as it has come to be known, is one of those ‘footnotes of history’ that invites consideration of the larger issues surrounding the settlement of the west. Of course, the whole question of relations with the native tribes is front and center. But other large events and issues are also relevant to the story – the Mexican War, North-South politics and slavery, the impact of the Civil War, military training and strategy, the roles of mining, emigration, and transportation. In short, in the Bascom Affair we have a microcosm of, and in some ways a metaphor for, the development of the west.